for the love of you, 2021.

[left] untitled (back II), 2020, 24 x 30", archival pigment print. [right] untitled (follow suit), 2021, 10 x 24", 18 x 32" with frame, archival pigment prints (triptych), burgundy suede.

untitled (back II), 2020, 24x30 ", archival pigment print.

untitled (follow suit), 2021, 10 x 24 ", 18x32 " with frame, archival pigment prints (triptych), burgundy suede.

[left] untitled (seeing eye to eye), 18 x 24", archival pigment prints (diptych). [middle] untitled (mask), 2021, 30 x 38", archival pigment prints (diptych). [right] mother spilling tea (three), 2020, 12 x 18", archival pigment print.

untitled (seeing eye to eye), 18 x 24", archival pigment prints (diptych).

untitled (mask), 2021, 30 x 38", archival pigment prints (diptych).

mother spilling tea (three), 2020, 12 x 18", archival pigment print.

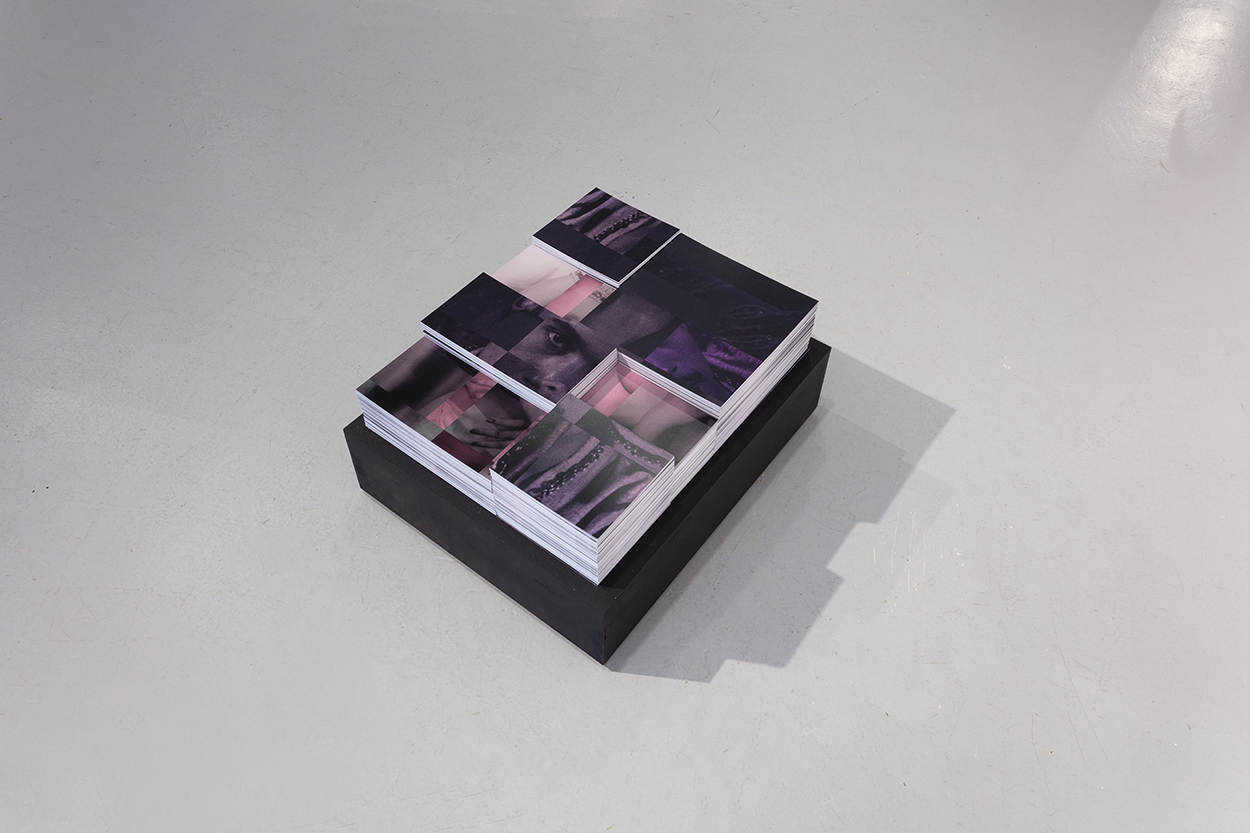

please don’t drive me, let me ride, 2021, fragmented prints on paper, 300 stacked sheets, black floating pedestal, looping sound, 9:39 minutes.

[left] untitled (playing suit), 2021, 10 x 32", 18 x 40" with frame, archival pigment prints (quadriptych), burgundy suede. [right] untitled (lighter), 2021, 24 x 30", archival pigment print.

untitled (playing suit), 2021, 10 x 32", 18 x 40" with frame, archival pigment prints (quadriptych), burgundy suede.

untitled (lighter), 2021, 24 x 30", archival pigment print.

In one of tarah douglas’s most memorable pictures, a woman presses close against her mirrored reflection, smiling freely at what might be an inside joke, or a passing memory of tender affection, or—keep it simple—just the sight of herself: startled by recognition into joy. It’s the kind of image that bats away interpretations just as quickly as it invites them—a work of generosity that nonetheless maintains a kind of privacy. The correspondence between photography and poetry is well-established: each is a technology that “captures” as a gesture toward adding more meaning to a world already dense and drastic with meaning; each, at its best and most humane, withholds, keeps a crucial kernel to itself, not stingily but as a way to hold attention—a way to court and offer love.

douglas is a photo-poet in this lineage, and a kind of crooner, too. The picture of the woman and the mirror brings names to mind—Narcissus, Snow White, Lacan—and dares you to contemplate social facts: her womanhood, the color of her skin, its possible histories. Something in the twinkle of her eye, though—the glint of a moist eye looks like a distant star, or a perfectly-placed daub of white paint—makes the picture wash over you, more felt than understood, like the smooth yelp of a falsetto. I heard from a good source that, until just a few days before installing this set of pictures, douglas was considering not including the picture of this face, these faces. In its giving, the thinking went, it might have given too much. I’m glad it’s here, but I see the possible problem. Elsewhere there are cosmetic masks and stark fingerpaint, promising identity but delivering disguise. This is as far from autobiography as it gets.

Think of those profoundly mysterious soul songs of the 70’s. Here’s Ron Isley, buzzing his falsetto as through the mouth of a flute, in the song “For the Love of You,” by the Isley Brothers, whom douglas cites as an inspiration:

Driftin’ on a memory

Ain’t no place I’d rather be

Than with you, yeah

Lovin’ you, well, well, well

Day will make a way for night

All we’ll need is candle lights

And a song, yeah

Soft and long

Isley sounds reflective and almost nostalgic—after all: memory but this could just as easily be a pleading bit of projection into the future, or the kind of in-the-moment narration we more readily associate with fiction in the present tense, or the temporal-dramatic break that opera achieves via the aria. douglas collapses time—and, therefore, phenomenological angle—in this way, in picture after picture. Look: a woman stands still, looking slightly to her left, in the middle of a courtyard full of wild and potted plants. The plants, in their profusion, suggest the presence of many more, just out of frame. The woman has her back to us and faces a corner—the corner should be a dead end but looks more like a portal. She could be remembering something, or chasing a loose thought, or, even in this pose of gentle refusal, making a subtle offer to the viewer. Stay, sit. Take, eat. Or consider this triptych: a cruciform pole with a ball at its peak; a black back blackly shadowed; some chairs and cloth drapings and curtains: white on white. These are color studies, yes, but also fertile snatches of a world that was, or is, or is to come. They’re evidentiary statements from a process that douglas shows but also hides. Call it staging or call it the occult.

Process: one way to read these pictures is to see them as documenting a search. douglas goes spelunking through archives and comes up gasping. Zora Neale Hurston, twentieth-century America’s great artist-folklorist, said this of the songs she went questing to recover: “The real spirituals are not really just songs. They are unceasing variations around a theme.” The same might be said of the simple vernacular mannerisms—old news made new—that douglas has retrieved and revivified according to a poetic logic. A series of hands, their carriage suggesting a silent, secret language of codes, or the recipe for an unusually potent spell. An almost unreadable sculpture of images, a collage of collages, faces and fabrics from the past, floating close to the floor and displaying the kind of “jagged harmony” that Hurston insisted was “what makes” the essence of the spirituals: I still have a piece of the piece—you can take from it, like a communicant takes a piece of the Body of Christ—in a pocket of the notebook in which I am writing, right now.

Here’s the poet Eve Ewing, in her poem “what I mean when I say I’m sharpening my oyster knife,” after a quote by Hurston, but also forecasting the transfiguring archival/imaginative work of an artist like douglas:

I mean

when I see something dull and uneven,

barnacled and ruined,

I know how to get to its iridescent everything.

Iridescent everything! That works for douglas, even when she’s working in black and white.

Think, if you will, of one more picture—one of douglas’s simplest and most beguiling. One teacup tilting thick, sparkling honey into another, and a pool collecting in a saucer beneath. You see a bit of a thumbnail—blue—and a slip of a pointer finger. Somebody’s doing this, and who cares why. It’s all covert recovery, all sweet sung spike and jagged harmony, all mysterious and freely offered gift. All love, for love’s own inscrutable sake.

Installation shots by Liz Calvi

SORRY WE MISSED YOU

Yale School of Art’s 2021 Photography MFA thesis exhibition

Green Hall Gallery, 1156 Chapel Street, New haven, CT. May 10 through 16, 2021

Featuring work by: Mickey Aloisio, Ronghui Chen, tarah douglas, Jackie Furtado, Max Gavrich, Nabil Harb, Dylan Hausthor, Annie Ling, Alex Nelson, and Rosemary Warren.

Exhibition identity by Nick Massarelli and Anna Sagström, Graphic Design MFAs ‘21.

Installation photography by Liz Calvi, unless otherwise oted.

SORRY WE MISSED YOU

Yale School of Art’s 2021 Photography MFA thesis exhibition

Green Hall Gallery, 1156 Chapel Street, New haven, CT. May 10 through 16, 2021

Featuring work by: Mickey Aloisio, Ronghui Chen, tarah douglas, Jackie Furtado, Max Gavrich, Nabil Harb, Dylan Hausthor, Annie Ling, Alex Nelson, and Rosemary Warren.

Exhibition identity by Nick Massarelli and Anna Sagström, Graphic Design MFAs ‘21.

Installation photography by Liz Calvi, unless otherwise noted.