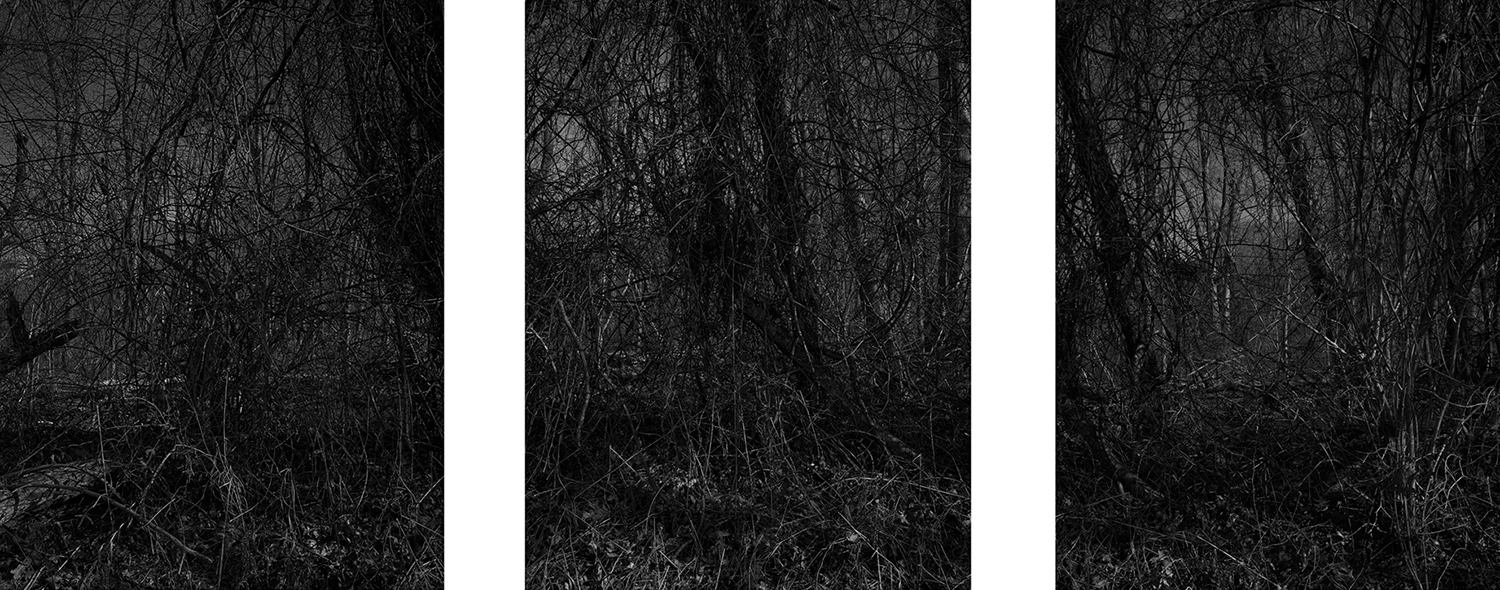

The monochromic triptych from the series of 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei (2021) by Chen Ronghui is a wordless poem written in the enriched language of landscape photography.

The assemblage consists of three sizable photographic panels. From right to left following the visual tradition of a Chinese handscroll painting, each view is a continuation of the previous scene of a shadowy landscape. At first glance, the branch-filled space appears to have blocked our way of entering the pictorial space. We are not given sufficient clues to unravel the world of entangled weeds and twigs, and there is no one in the woods with whom we can identify. The darkness and loneliness exuding from the photographs disorient our sense of space and time.

But where there is shadow, there must be light: the sun’s reflection enters the dark woods. Actively following the sunlight our eyes begin to “see through” the paradoxical world that is full and empty at the same time.

The series of 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei was inspired by an eighth-century Chinese poem, The Deer Enclosure, and its multiple modern translations from the West. The great poet Wang Wei (701-761) named the verse after a real place dedicated to a group of deer within his reclusive, picturesque residence. The celebrated four-line poem sprang to Chen’s mind when two deer approached him in East Rock, New Haven. Past and present, East and West, and poetry and photography, were re-oriented and compressed into the triptych, driving us to ruminate on what has been lost in the mists of time, translation, and remediation.

Empty mountains: /no one to be seen.

Yet-hear/human sounds and echoes.

Returning sunlight/enters the dark woods;

Again shining/on the green moss, above.1

1. Translated by Gary Snyder in 1978. Eliot Weinberger, Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei: How a Chinese Poem is Translated (Asphodel Press, 1995), 42.

In addition to poetry, Chen borrows the “ways of seeing” of traditional Chinese visual culture to enrich the language of landscape photography in America. The artist adapted the shifting perspectives found in Chinese landscape painting to photography by taking dozens of images of a scene, each with a different focus, and digitally “stacking” them together. The process has introduced a hybridized “way of seeing”—multi-focuses within a single pictorial plane of photography. This may bewilder us since we are unaccustomed to this visual experience; we are unsure of our relationship to, and position within, the photographic space. The landscape photography by Chen no longer places us at the center of the universe, the illusion constructed by the linear perspective. In a way, the multi-focuses have freed us from the prescribed, classical way of seeing: we now look at the landscape as we read the poem. The two unfold as time flows; the poetic imaginary comes into existence slowly as our focus moves from line to line, and from branch to branch. Deer, a spiritual creature in Chinese culture, inhabits the space between the lines of Wang Wei’s poem and in the depth of the woods in Chen’s landscape photography.

The 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei is a culmination of the artist’s photographic experimentation at Yale and the starting point of a new phase of artistic adventure.

ronghuichen.com

@chenronghuistudio

SORRY WE MISSED YOU

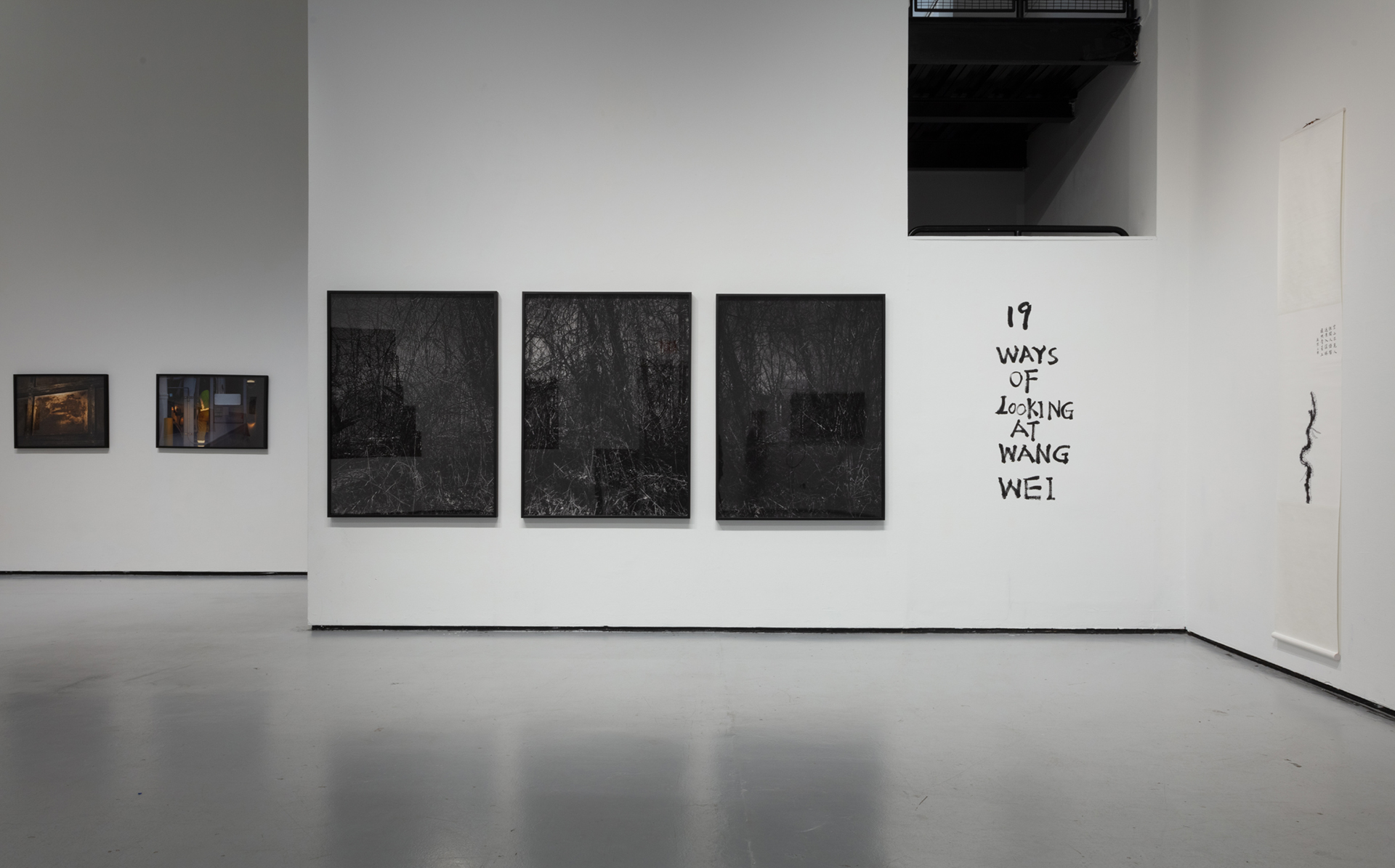

Yale School of Art’s 2021 Photography MFA thesis exhibition

Green Hall Gallery, 1156 Chapel Street, New haven, CT. May 10 through 16, 2021

Featuring work by: Mickey Aloisio, Ronghui Chen, tarah douglas, Jackie Furtado, Max Gavrich, Nabil Harb, Dylan Hausthor, Annie Ling, Alex Nelson, and Rosemary Warren.

Exhibition identity by Nick Massarelli and Anna Sagström, Graphic Design MFAs ‘21.

Installation photography by Liz Calvi, unless otherwise oted.

SORRY WE MISSED YOU

Yale School of Art’s 2021 Photography MFA thesis exhibition

Green Hall Gallery, 1156 Chapel Street, New haven, CT. May 10 through 16, 2021

Featuring work by: Mickey Aloisio, Ronghui Chen, tarah douglas, Jackie Furtado, Max Gavrich, Nabil Harb, Dylan Hausthor, Annie Ling, Alex Nelson, and Rosemary Warren.

Exhibition identity by Nick Massarelli and Anna Sagström, Graphic Design MFAs ‘21.

Installation photography by Liz Calvi, unless otherwise noted.